This spring, a diverse team of ocean scientists headed to the middle of the Pacific Ocean, seeking to explore the vast and mysterious home of one of the world’s top ocean predators: the white shark.

Guided by the sharks and their need for a steady supply of food, the researchers sailed into the heart of what was once deemed an oceanic “desert.” They discovered that the open Pacific, particularly an expanse dubbed the White Shark Café, teems with abundant and unusual life forms—organisms that may help explain the fascinating behaviors of white sharks on the high seas.

“The Café is far from the desert it was thought to be,” says Aquarium research scientist Dr. Sal Jorgensen. “It is home to an abundance of life that satellite imaging is not detecting. In fact, for white sharks, it is more of an oasis.”

The White Shark Voyage team embarked from Honolulu for a month-long journey aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s R/V Falkor and traveled east to waters halfway between Hawaii and Mexico.

Headed by principal scientist Dr. Barbara Block of Stanford University, the research team aboard the Falkor included marine biologists, engineers and oceanographers from Monterey Bay Aquarium, Stanford, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), University of Delaware, NOAA, Montana State University and ocean tech innovator Saildrone.

While no one knew what they’d find, everyone hoped to gather insights about what might be driving the behaviors of white sharks, and what role this offshore habitat plays in the lives of these apex ocean predators.

Location services for white sharks

In preparation for the expedition, the team deployed 34 tags on adult white sharks off the coast of California in the fall of 2017, knowing that a few months later those same sharks would swim toward the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The tags were programmed for release during the month the Falkor was in the Café, delivering their stored data to orbiting satellites.

Following the blips emitted from the tags as they popped to the surface, the Falkor made its way into the heart of the White Shark Café, sampling marine life and ocean conditions wherever the tags surfaced.

Over the course of the month, the team recovered 10 of those unbelievably small pop-up satellite tags from the open ocean.

“Tracking and then recovering released tags from white sharks across a swath of ocean about the size of New Mexico required incredible precision and patience from the team and crew,” explains Aquarium research fellow Paul Kanive.

“We were trying to retrieve something floating in the ocean smaller than the size of a light bulb, with an 80-meter ship.”

The effort was worth it.

“In one month at the Café, we doubled the amount of tagging data in our collection.” Sal says. “The trip was hugely successful in that regard.”

Deep data discoveries

The pop-up tags provided locations for the team to collect a wide variety of samples and data that will eventually help create 3-D diagrams of the Café’s living, underwater structure. For example, they gathered eDNA—water samples taken from different depths, providing microscopic traces of skin, feces and mucus from all the different organisms that live in the Café.

Sequencing and identifying the genetic codes from this ”DNA soup” will help reveal which animals move throughout the waters, and where.

The researchers also towed midwater net trawls (1,500 feet deep) to gather species that form the lower rungs in the food ladder, such as lightfish and lanternfish—creatures that represent the largest biomass of vertebrates on the planet.

These small, shimmering gonostomatids and myctophids, whose light-producing organs help them hunt and evade predators, take part in the world’s largest collective migration: a vertical daily movement, up to the surface and back down again. Larger predators exploit this abundant food source, creating an entire, oscillating ecosystem.

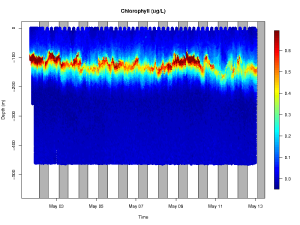

“It’s a massive daily commute from the deep sea, to the warmer surface waters under the cover of darkness, and then back down again by dawn,” explains Sal. “These midwater species—including shrimp, squid, jellies, tunas and sharks—together form a massive living blanket, known as the deep scattering layer, and this whole soupy layer travels up and down together.”

Each member of the team helped quantify the enormous movement of life up and down the water column in the Café.

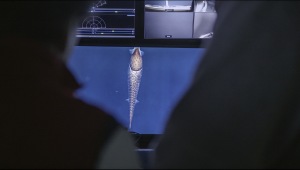

Pioneering deep-sea biologist Dr. Bruce Robison of MBARI directed the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) SuBastian, illuminated elusive life forms in the deep ocean, and recorded them on film to share with the world.

Using additional data from drones that sail on the ocean’s surface, the researchers were able to match the movements of female white sharks to the daily commute of lower-trophic level animals throughout the Café. This confirmed the team’s previous hypothesis that mature female white sharks are likely targeting food items within the deep scattering layer.

As Stanford University Barbara Block explains: “We found a high diversity of deep-sea fish and squids (over 100 species), which in combination with observations made by the ROV and DNA sequencing, demonstrate a viable trophic pathway to support large pelagic organisms such as sharks and tunas.”

In other words, the Café is far from the desert it was thought to be. And, Sal notes, it is home to an abundance of life that satellite imaging is not detecting. That’s because, he said, in the Café the base of the food ladder—the plankton that harvest energy from the sun—is concentrated at depths beyond the reach of satellites.

Male shark behavior in the Café remains mysterious, Sal noted. Their diving patterns differed. They moved up and down six times faster and more frequently than females, and concentrated their efforts in a preferred depth band, both day and night.

The data downloaded from the recovered tags will allow researchers to conduct more in-depth analysis. They hope it will shed some light on whether the males are feeding differently than females, or perhaps creating opportunities to mate with them.

A legacy of white shark research

The expedition to the White Shark Café builds on over 20 years of white shark research by the Aquarium, Stanford and other partners around the world. The white shark has long captured public interest, evoking awe and imparting a sense of prehistoric wildness that is greater than us.

“It’s been fascinating to learn more about their activities. Through the tagging that the Aquarium sponsored, the white sharks led us to one of the most overlooked and under-studied places in the ocean,” Sal says.

“It’s been fascinating to learn more about their activities. Through the tagging that the Aquarium sponsored, the white sharks led us to one of the most overlooked and under-studied places in the ocean,” Sal says.

“After years of studying the tagging data, we began to notice incredible diving behavior and came to realize that they spend most of their life here, in the middle of the ocean and at depths where sunlight ceases to reach, a place called the ‘twilight zone.’ This trip was about following the sharks out there to see and describe this ecosystem.”

Prior to this offshore trip, multiple teams of scientists spent countless hours tagging and tracking white sharks along the California coast. They dedicated months to analyzing data, and years to illustrating the complexities of white shark behavior, which explain their life history strategies such as pupping and foraging.

“These white sharks are now showing us that there is something truly important about the open ocean,” says Sal. “They’ve heralded the need to ask new and better questions about how apex ocean predators thrive in their underwater world.”

Answering those questions inevitably requires that we consider how best to protect critical ocean places like the White Shark Cafe. These places may be essential to maintaining healthy populations—not only of ocean predators, but of all marine life in the world’s largest habitat.

—Athena Copenhaver

Featured white shark photo courtesy Stanford University.

Learn more about Monterey Bay Aquarium’s work to conserve and protect sharks.

6 thoughts on “For white sharks, an oasis, not a desert”