The idea seemed like a long shot: Build a video camera that could attach to a great white shark for months at a time, withstand ocean depths of more than 3,000 feet, and sense the shark’s movements to selectively capture footage of its behavior.

But Monterey Bay Aquarium Senior Research Scientist Salvador Jorgensen, a white shark expert, thought it might have a chance if he joined forces with the talented minds at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI).

“Some of the engineering team said it was an impossible job,” MBARI Engineer Thom Maughan recalls with a smile. “But I’m attracted to those opportunities.”

So Thom and Sal teamed up on a high-tech mission: to capture video footage of great white sharks in their most mysterious habitat.

Intrigue in the open ocean

Great white sharks cruise the shorelines of the Central Coast, Southern California and Baja California during fall and winter. But just before spring, they disappear from the California coast. For decades, scientists puzzled over their whereabouts.

One clue was revealed in a landmark 2002 paper. A team of scientists — including Barbara Block and Andre Boustany of the Tuna Research and Conservation Center, a joint project of Stanford University and the Monterey Bay Aquarium — tracked great whites using electronic tags. They were surprised to find that some of the sharks traveled more than a thousand miles west of Baja California, and stayed for months in a remote region of the Pacific Ocean.

Their motive for leaving the productive California Current was, and still is, unknown.

“Why would the sharks leave this highly productive area?” Sal wonders. “Calories are just sitting on the beach here, in the form of blubbery elephant seals.”

Electronic evidence

Sal and colleagues at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station, the University of California, Davis, and Point Reyes National Seashore set out to find answers. They outfitted great white sharks with electronic tracking tags to learn more about where they go, and how deep they dive.

One resulting paper, published in 2009, dubbed the sharks’ remote Pacific hangout the “White Shark Café.”

Data from the tags revealed some fascinating behaviors. Upon arriving at the Café, male sharks perform what Sal and Thom call “oscillatory diving” — racing up and down between depths of 150 and 600 feet, sometimes 150 times a day! They swim like this day and night, for weeks on end. But why? In 2012, the team of scientists hypothesized they’re doing one of two things: either hunting a seasonal food item, or finding mates.

The name White Shark Cafe seemed even more fitting. “A café is somewhere you might go to get a bite to eat,” Sal says, “but it’s also a place where you might meet someone special.”

A mission to Mars

To get to the bottom of this strange behavior, Sal needed to see what was going on at the White Shark Café — from a shark’s perspective. And that would require some very specific technology.

For starters, he’d need a video camera. The camera would need to have a long battery life, and be small enough to clip to a shark’s fin. It would have to be waterproof, even more than a half-mile below the ocean’s surface, and able to film in low-light conditions. Researchers, working from boats near the Farallon Islands, would clip it to the shark’s dorsal fin, and the low-impact clamp would remain on the shark for almost a year.

The camera would need to be able to “sleep,” conserving battery life and recording capacity, while the shark traveled to the café. Then it would have to kick into action once the shark started speed-diving — the intriguing behavior scientists want to understand.

After all that, the camera would have to have a time-release mechanism allowing it to detach cleanly from the shark’s fin at just the right time, float to the surface, and expose an antenna that tells an ARGOS monitoring satellite its location. The satellite would send an email to Sal’s team, who would go out in a boat to retrieve it. Only then could they take a look at what the camera documented.

“It’s like a mission to Mars,” Sal says.

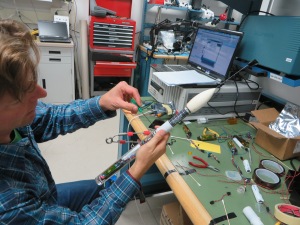

By that metaphor, Thom is the shuttle engineer. Over the past few years, he’s figured out how to make the Café Cam waterproof, keep it small, prevent it from corroding, and make it easily attach and detach from the shark. He’s even come up with a way to prevent organisms from growing over the lens and blocking the light.

“It’s easy for a biologist like myself to dream up questions we’d like answered with technology,” Sal says, “but somebody has to actually push the envelope and make that happen. And that’s where the top-notch ocean engineers at MBARI come in.”

Final touches

Thom and Sal engaged other engineering partners, including Desert Star and Custom Animal Tracking Solutions, to help achieve their ambitious goal of capturing video footage of great white sharks in the remote Pacific Ocean.

In Thom’s hands, the Café Cam has become a real, working prototype. Sal’s team has conducted one-to five-day tests of the camera on sharks in coastal waters. Each time, they’ve made improvements to its design.

But they still need to smooth out some kinks — making the camera even smaller, and programming it to record at just the right time. The final version of the Café Cam will be about the size of a remora, the “sucker” fish that sometimes takes a ride on sharks, Sal says.

It’s a tough challenge, but Sal and his colleagues are experienced with electronic shark tags. In addition to the ones that track location and diving depth, they’ve used tags that are swallowed by sharks and record activity from inside the stomach, before being regurgitated and retrieved.

Sal’s team aims to conduct more Café Cam tests along the Central California coast this fall. The moment of truth may come in the fall of 2017, when — if all goes according to plan — a shiver of white sharks will carry cameras deep into the heart of the Pacific Ocean to reveal their diving secrets at last.

Featured image: The view from a great white shark’s perspective, captured on a prototype of the Café Cam.

Reblogged this on Diana LaScala-Gruenewald.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing things theses Scientist are coming up with. I have always been fasinated with sharks. The mysteries that they hold is truly amazing. Keep doing what you guys are doing. I also really enjoy every experince I get when I visited the Auquarim.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me alegra saver que estan llegando tiburones blancos a Monterrey.

Con Los canbios del clima de la Tierra savemos que tanbien hay canbios de clima en el agua por lo tanto devemos ser cautelosos Para Los nuevos visitantes que problablemente abra en el mar en un futuro muy sercano.

LikeLiked by 1 person